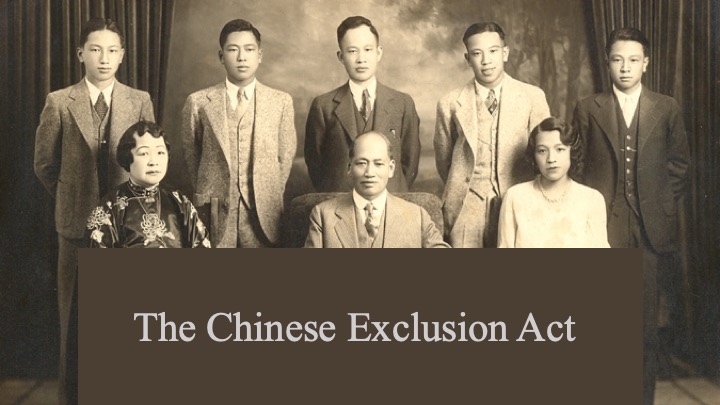

The Chinese Exclusion Act

In 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed a law that would tear families apart, separating children from parents, wives from husbands. Children might never know their fathers, wives were abandoned to rear those children alone in a country thousands of miles away, and husbands committed themselves to long hours of harrowing manual labor in the United States in order to send money back. Many would never go home again. The law, the first in American history to drastically restrict immigration, would remain in effect for more than half a century.

In 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed a law that would tear families apart, separating children from parents, wives from husbands. Children might never know their fathers, wives were abandoned to rear those children alone in a country thousands of miles away, and husbands committed themselves to long hours of harrowing manual labor in the United States in order to send money back. Many would never go home again. The law, the first in American history to drastically restrict immigration, would remain in effect for more than half a century.

In 1943 Congress passed and President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the bill that repealed the exclusion laws against Chinese immigrants. The new law set the immigration quota for China at just over 100 visas per year.

Arthur Ainsberg has been working on this subject for several years. Like his other projects, he has focused on a topic that few other people know about.

“How I came to this story is fascinating. I had always wanted to write a book on the Supreme Court because of the mystique of the court, but I didn’t want to get sued. The way not to get sued is to write about dead people, so I wanted to find a Supreme Court case that happened in the past and that would be an emotional kind of story,” he says.

“There are very few books on individual Supreme Court cases. Even though the court is more than 200 years old, I don’t think there are more than a dozen books on individual cases.

“So what do you if you want to write a book about the Supreme Court? You go on Amazon. You buy every book ever written about the Supreme Court. And one afternoon you get a lot of boxes delivered. That night I started reading Supreme Court cases.

“The year is 2010, so now I’m 63 years old. One night I’m reading a book on Constitutional law. I come across a section called the Chinese Exclusion Act thesis. And I’d never heard of the act!

“I literally put the book down, go into my den to Google the Chinese Exclusion Act, and I say, oh, my God, because I’ve never heard about it. It was never in my high school or college textbooks on American history. That was the beginning of my interest, which continues to this day.”

It is a difficult subject to research. “Most of the Chinese workers who came over were male, and most of them were totally illiterate. None of them kept diaries. That is a problem.

“The immigrants tried to bring over women, but Congress said they couldn’t, so there’s a society in San Francisco in the late 1800s called the Bachelors Society because all of these Chinese men would come over and they had no family. They literally spent their whole life here and never became a citizen because they couldn’t become a citizen. They sent money back and they lived as bachelors. It’s a very sad story, this whole story of the Chinese-American. And it fits very well into the whole immigration story that we’ve all been talking about.

Ainsberg’s research became the focal point for an exhibit at the New York Historical Society in 2014 ago called Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion, which was one of the most well-received exhibits ever at the society. “I have a lot of research,” he says, “but it’s far from done—I’m working on a book on the subject.” He is frequently called upon to speak on the topic and has a prepared lecture with slides that he presents.

It’s still a work in progress, but Ainsberg has already derived rewards from his efforts. “I got just tremendous, tremendous satisfaction from the exhibit at the New York Historical Society,” he says. “And a very well-known documentarian became aware of my research and did a documentary on the subject.”